This weekend, I attended the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies annual conference in Oxford. It was an enjoyable and thought-provoking few days, in which I met some lovely people, learned a lot and had a great many interesting and helpful conversations, not all of them just about the 18th century. It was my first time at BSECS, and I was there to participate in the panel ‘Public Mourning and Private Grief, c.1770-1820’. Last summer I was fortunate enough to undertake a curatorial placement at the Museum of London, funded by LAHP, to enhance catalogue entries and research funerary objects, mainly jewellery, from the Decorative Arts collection (more on this another time). Dr Danielle Thom, Curator of Making at the Museum of London and wise placement mentor, suggested that BSECS would be a good opportunity for a panel on 18th century funerary material culture and also contacted Emily Knight, who has recently submitted her thesis on posthumous portraiture in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Emily Knight (V&A) – The popular for the personal: visual and literary quotation in posthumous portrait miniatures

Sarah Hoile (UCL) – ‘Sacred will I keep thy dear remains’: late 18th century mourning jewellery

Danielle Thom (Museum of London) – ‘I take ‘em when the tear’s in the eye’: emotion, obligation and funerary sculpture

The focus of the panel, both in terms of the subjects discussed and the time period, meant that many links were immediately apparent between all three papers, which made for a stimulating and productive session which I enjoyed very much. There is so much that I could write about the questions raised within and between the papers, and I have a great deal to think about as I work on the rest of my thesis. In particular, the status of commemorative objects as private and/or personal; the choices/tensions/connections between asserting status and familial obligation or the expression of emotion; and the ways in which different types of objects, images and texts (funerary and otherwise) influenced each other.

The other papers, and the discussion that followed, really reinforced for me the importance of considering different types of funerary objects of this period in a wider context. As Emily’s paper so deftly demonstrated, objects were influenced by, and created from, a range of sources, some directly personal and others selected as particularly resonant or appropriate (e.g. poetry). On the day after the panel, though, here are just a couple of aspects of memorialisation in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (which certainly don’t cover the full scope of the papers and discussion), which I have been reflecting on this morning, and some of the questions they suggest.

Timing

The question of timing of the purchase, creation and use of different forms of memorialisation is a really interesting one. One of the portrait miniatures discussed in Emily’s paper was commissioned during the same month as the death of its subject, for example, though these were, of course, individually-made items which would have taken time to complete. Many of the mourning objects I talked about would have been pre-made and personalised with an inscription at short notice, possibly very soon after the death they commemorated, though some were clearly adapted or created for a particular individual, such the memorial pendant for a clergyman, Rev. William Clark (d.1786), which includes a church in the background, uniquely in this collection.

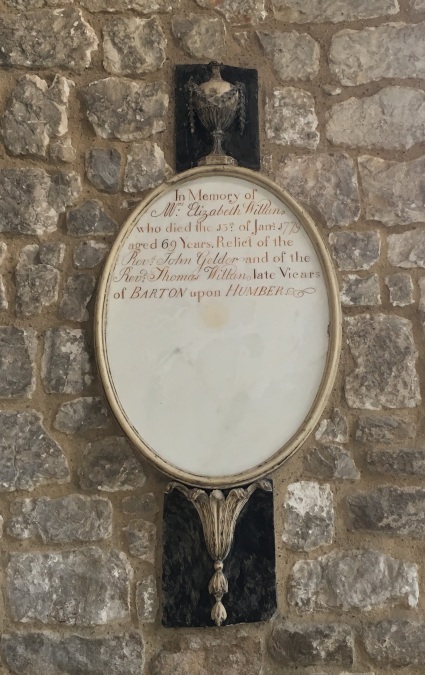

As the title of Danielle’s paper suggests, timing was significant in the business of selling sculptural monuments. ‘I take ‘em when the tear’s in the eye’ was attributed to the sculptor Joseph Nollekens by his embittered and unreliable biographer, suggesting a rather cynical approach to the commercial side of commemoration. While some commissions were made by the very recently bereaved, they could, in some cases, take years to complete, due to the scale of the monument or to logistical issues, and an example of buyer’s remorse from one of Nollekens’ customers served as a reminder that both feelings and finances could change in the meantime.

What impacts did the timing of the purchase of commemorative items, whether bespoke or ‘off the shelf’, have on the choice of styles, inscriptions, size and cost? At what point were they available for managing or signalling grief? How did this affect the role of these objects within the mourning processes of the bereaved?

Children

All three papers included objects associated with the deaths of young children. Emily discussed a locket commemorating a child for which a popular image had been adapted, as no portrait of the child had been made during his short life, a fascinating example within her exploration of the ways in which posthumous portrait miniatures included recycled and recontextualised quotations, both visual and literary. In this case, the child’s hair had been arranged in the back of the object, preserving something very personal of a cherished son, who was otherwise represented visually by a substitute, though clearly meaningful, image.

In my paper, I looked at a ring from the Museum of London’s collections which commemorates the seven children of the Woodmason family, who died in a fire at their home in London in 1782. Both the design and inscriptions are unusual, which I suggested were a distinctive response to this tragic loss, for which the more usual designs were not considered adequate. Other objects commemorating children were of more conventional design, such as the bracelet slide commemorating ‘L B’ who died, aged 5 months, in 1778, which I included in my presentation as an example of typical mourning jewellery in this period.

Danielle highlighted the extraordinary monument to Penelope Boothby by Thomas Banks, in Ashbourne Church, Derbyshire (1793), which depicts the child lying as if sleeping with, touchingly, her arms held in front of her.

How do these objects inform or complicate our ideas about commemoration, particularly in considering the influences of obligation and grief? Did the commemoration of children differ from that of adults? In what ways? And what might this tell us more broadly about commemorative choices, designs and the use of these objects?

The inter-disciplinary nature of BSECS made it a great forum for bringing together papers which raised and considered these and many other questions relating to mourning and commemoration in the 18th century, and an audience with diverse interests and experience to discuss them. It has given me plenty to consider, including identifying ways in which to continue these conversations, and a boost at the start of the year to press on with the final part of my PhD.